South Africans’ Access to Courts and Correctional Services: What the Data Reveal

How easily can South African households access the justice system – and what do they think of it once they do? A new report released by Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), the Governance, Public Safety and Justice Survey (GPSJS) 2024/25, paints a revealing picture of citizens’ engagement with the country’s courts and correctional services.

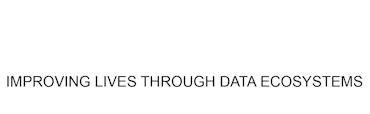

In the past year, nearly one in five households in the Northern Cape (17,6%) reported visiting a court – the highest rate in the country. For most South Africans, getting to a magistrate’s court is relatively manageable, with about 61% saying it takes them less than 30 minutes on average. Despite this physical accessibility, conversations about the justice system remain limited: more than 40% of household heads said they never discuss court-related matters with family or friends, a pattern unchanged since 2018/19.

When it comes to perceptions of fairness, about 44,8% of respondents expressed satisfaction with how courts handle offenders, citing that “sentences are appropriate to the crime”.

How Individuals Experience Justice in South Africa

Zooming in from households to individuals, the data provide a closer look at who actually interacts with the courts – and why. According to findings aligned with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16.3.3, which tracks access to justice and the resolution of legal problems, fewer than 5% of South Africans aged 16 and older reported going to court during the 2024/25 period. The Northern Cape leads with the highest individual attendance, followed by the Western Cape and Free State.

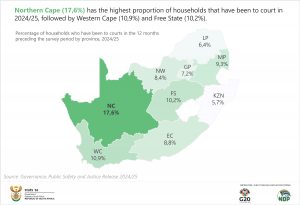

Court visits happen for a range of reasons – and these patterns are shifting. Around 22% of individuals attended court as those bringing charges or litigants, up from 16,6% in 2018/19, while nearly 21% went as the accused. Support for family or friends remains common, though this has dropped from 29,2% in 2018/19 to 23,0% in 2024/25. Attendance for civil or administrative cases such as custody, divorce, or eviction has also shown an upward trend.

Language and understanding – key indicators of fair trial access – remain strong. More than nine in ten people were able to use a language they understand well during proceedings (94,8% in 2018/19 compared with 92,9% in 2024/25).

Who Represents South Africans in Court – and How Satisfied are They?

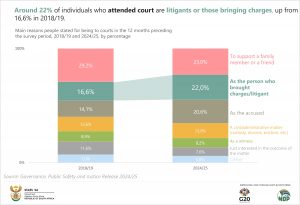

Representation plays a crucial role in shaping people’s courtroom experiences. In 2024/25, about three-fifths (62,7%) of individuals represented themselves – a notable decrease from 69,3% in 2018/19. Legal representation through Legal Aid South Africa grew modestly, from 18,3% to 20,8%. Private legal representation, on the other hand, declined from 15,5% to 12,9%, while roughly 17% were represented by state prosecutors in 2024/25.

Satisfaction levels varied by type of representation. In 2018/19, individuals represented by Legal Aid lawyers reported the highest satisfaction rate (89,3%), but by 2024/25 those represented by private lawyers were most satisfied at 94,8%. Self-representation satisfaction also rose sharply – from 86,1% in 2018/19 to 92,9% in 2024/25 – suggesting growing confidence among individuals navigating the system on their own. The lowest satisfaction (75%) was recorded among those represented by paralegal officials.

Awareness of the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) remains limited, with only 34% of people aged 16 and older saying they know about it. Men, those aged 35–49, and individuals with post-school qualifications were the most informed. Among those who were aware of the NPA, nearly half (48,7%) correctly identified its main function as prosecuting accused persons, followed by assisting police investigations (25,8%) and presenting evidence in court (13,1%).

Rehabilitation and Reintegration

Rehabilitation and reintegration are central to transforming offenders into law-abiding citizens. The Department of Correctional Services provides a range of programmes, from incarceration and security to rehabilitation and social reintegration, aimed at preparing offenders for life after prison.

The data reveal that around 3% of households reported being victims of crime where the perpetrator was arrested and jailed in 2024/25. Of these cases, only 36% of the accused were released on parole. Communication between correctional services and victims remains an area of concern – less than 60% of households said they were informed of the parole hearing, and among those who were notified, nearly one-fifth (19,1%) did not attend.

Public sentiment towards the correctional system is mixed. About 35% of households said they were satisfied with how correctional services grant parole, while 44% expressed satisfaction with the rehabilitation of offenders.

Public Attitudes: Are We Ready to Welcome Former Prisoners?

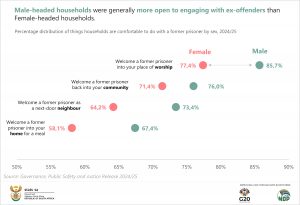

Rehabilitation is only half the story – reintegration is the true test of success. According to the data, male-headed households were generally more open to engaging with ex-offenders than female-headed households. Across three out of four questions, more than 70% of male-headed households expressed comfort with welcoming a former prisoner back into their community, place of worship, or even as a next-door neighbour.

Men were also more likely than women to say they would offer employment to, or marry, a former prisoner – pointing to subtle but important differences in how South African households view second chances.

Together, these findings offer a broad look at South Africa’s justice journey – from the courtroom to the correctional centre, and finally, to the communities where reintegration takes place. They reveal not only the progress made in access and fairness, but also the societal attitudes that will shape the country’s path toward a more inclusive and restorative justice system.

For more information, download the full report here.